Light-matter strong coupling

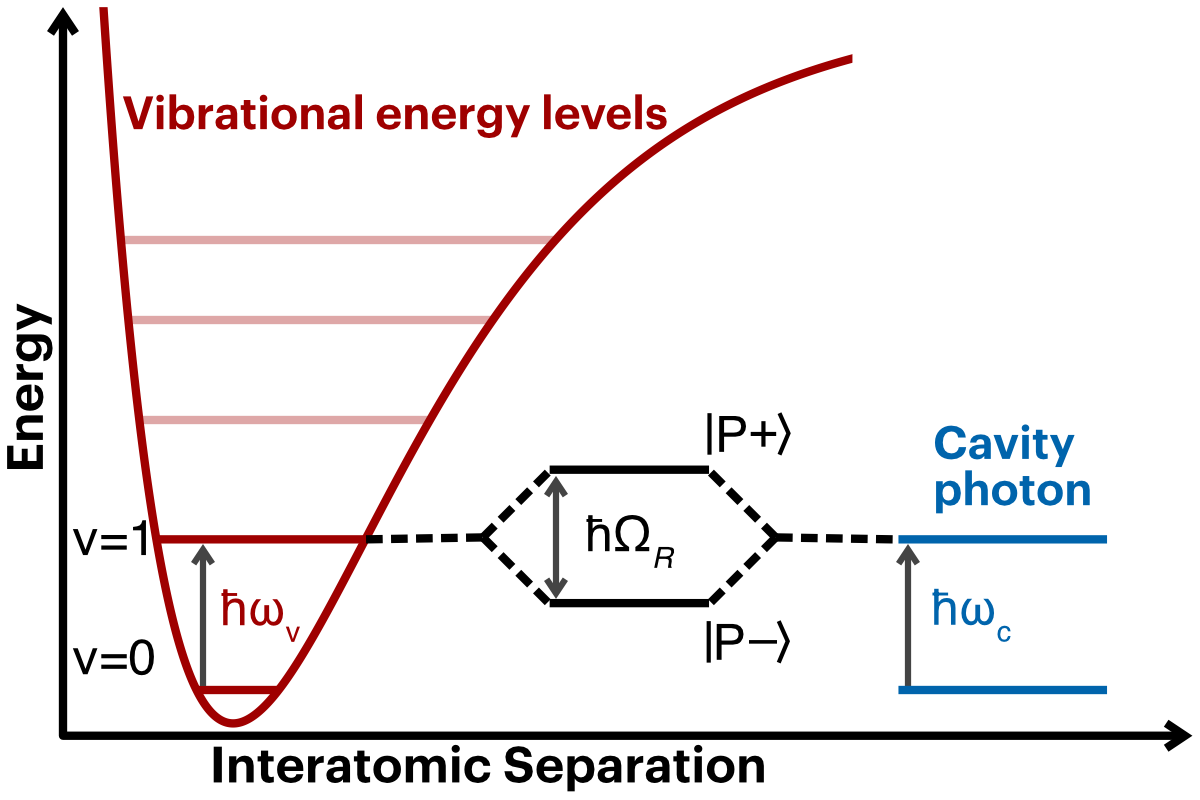

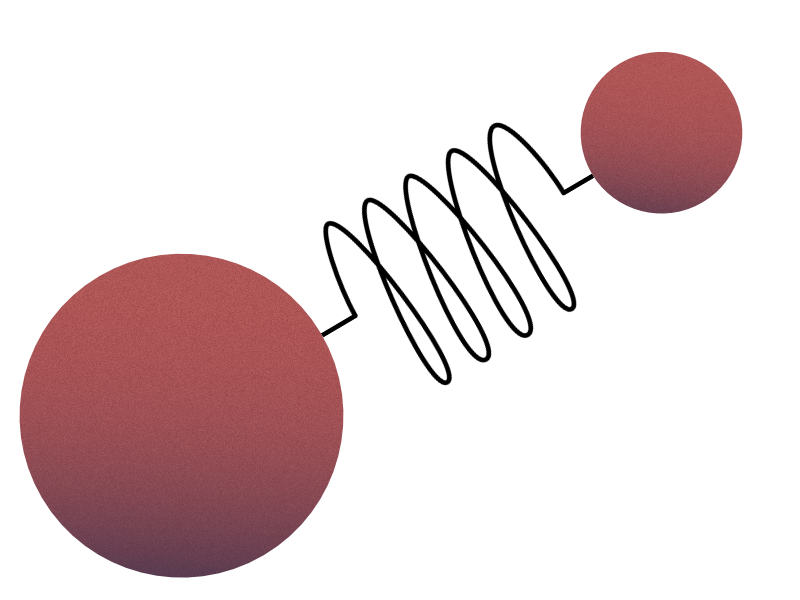

The bonds of molecules vibrate. They stretch, they twist, and they rotate kind of like when two balls are attached to a spring. Just like the balls-and-spring can be stretched and compressed faster or slower, so can molecular bonds. The stretching frequency is associated with an energy — the more energy you put into the spring, the faster it will stretch and compress. In a molecule, you can directly excite a molecular bond with light.

When matter interacts with confined light, the two can couple together. Why would this be the case? Light in free space can of course be absorbed by the molecule (it might be absorbed by the bond), but the molecular vibration will eventually decay and the light will be re-emitted back into free space. If you confine light, say, by placing two mirrors face-to-face, then you make a standing wave. Two people holding opposite ends of a rope and waving it up and down is an example of a standing wave. At a slow speed you just get a single arc going up and down. If you wave a little faster, the structure breaks down and the rope is all over the place. But go at just the right frequency, and you get two arcs going in opposite directions (one up and the other down), with a node in the middle that doesn't move. You can keep going with more energy as long as you don't tire out! Think of the opposing mirrors as the two people holding the rope. The light bounces back and forth between them and, just like with the rope, the standing light wave can only exist at certain frequencies.

When the frequency of the light is the same as the vibration frequency of the molecule, then the two can couple. The molecule absorbs the light (a photon) and re-emits it back into the cavity. Then it gets re-absorbed by the molecule and the cycle repeats until the photon leaks out of the cavity or decays into the molecular bath.

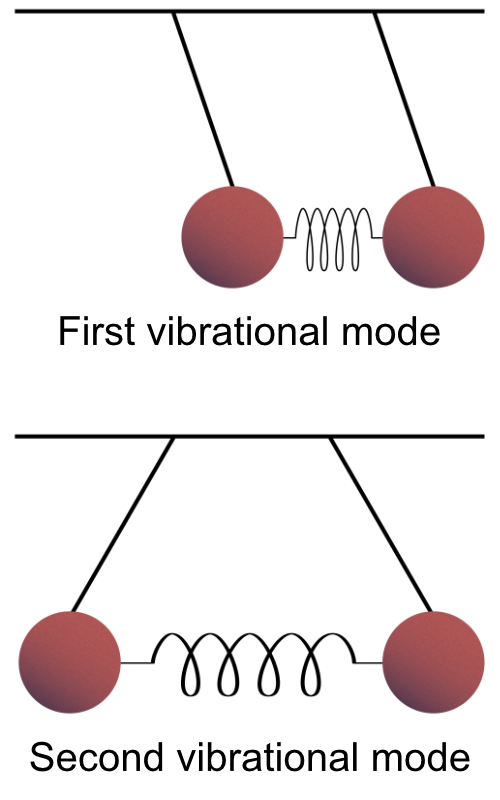

Light-matter coupling is analogous to two pendulums attached by a spring. Separate, each pendulum can oscillate at its own frequency independent of the other. Once they are attached by a spring, then there are two "resonances". They can either swing together: going together to the right, then to the left. Or they can swing opposite one another: they swing apart and the stretched spring forces them back together, and the now compressed spring pushes them apart again. These are two "normal modes" of the coupled pendulum. The confined light and matter, when coupled together, behave much like the coupled pendulum (details of the physics here).

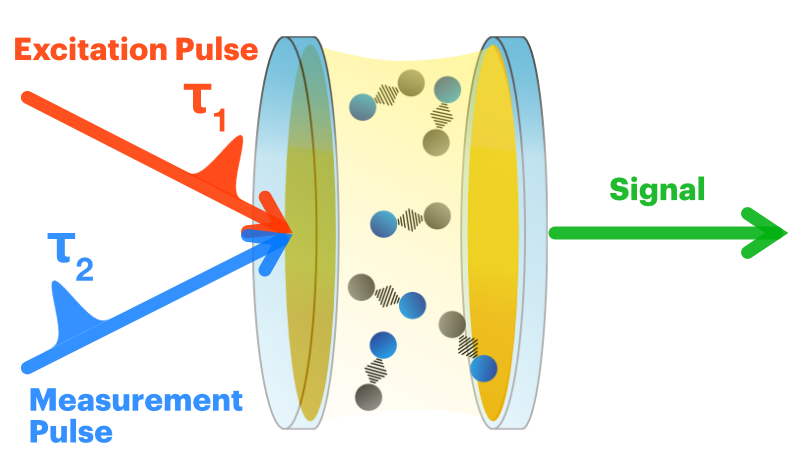

What is different in the coupled case versus just the molecule or cavity alone? And how long do the coupled states last? These questions require ultrafast lasers. Since we are looking at molecular vibrations, we also need the light to be in the mid-infrared region. The power of an ultrafast laser is in pulses that repeat at a certain rate. The temporal width of a pulse determines what kind of processes you can study. Molecular vibrations (once excited) decay very rapidly — on the order of pisoseconds (10-12 s) — so in order to see them a femtosecond (10-15 s) pulse width is required.

The experiment goes like this. An initial pulse is sent to excite the system — we put some energy into the light-matter coupled system. Then, while it is decaying, we send in a second pulse which then gets information about the system at some later time. This second pulse makes its way to a detector, which converts the light to an electrical signal that we can record. It's kind of like a strobe light and camera. You flash a light on the subject and then snap a picture. In fact, if you want to take a picture of a fast-moving subject (a bullet going through an apple), you need a lot of light and a very fast shuttter speed. This is very similar to the femtosecond excitation pulse-measurement pulse process.

Why study interactions between molecular vibrations and light? One of the most exciting things about these systems is that they can be used to modify chemical reactions. There are already demonstrations of this happening, but nobody knows *how* it happens. My goal is to figure out the fundamental properties of vibration-light coupling so that the chemistry might be explained.